Decoding the Lines: A Comprehensive Look at 1D and 2D Barcodes

Posted by Advanced Automation on Mar 23rd 2025

Barcodes have become an indispensable technology in the modern world, serving as a ubiquitous system for product identification and efficient data capture. From the simple act of scanning groceries at a checkout counter to the complex logistics of global supply chains and the critical tracking of medical information, barcodes play a vital role in streamlining operations and enhancing accuracy across numerous sectors. While the familiar linear barcodes have been a mainstay for decades, the emergence of two-dimensional barcodes has introduced a new level of capability and versatility. This article will delve into the fundamental differences between these two barcode types, exploring their history, structure, various forms, common applications, and the key factors to consider when choosing the appropriate barcode for a specific need.

A Look Back: The History of Barcodes

The concept of the barcode originated in 1948 when Bernard Silver and Norman Joseph Woodland, then graduate students at Drexel Institute of Technology, sought to address a request from the president of a local food chain to automate the process of reading product information during checkout . This initial motivation to improve efficiency and speed up retail transactions continues to be a significant application for 1D barcodes. Inspired by Morse code, Woodland conceived the idea of extending the dots and dashes into a series of bars and spaces of varying widths, which could be read by a machine . Their early work culminated in a patent application in 1949 for a "Classifying Apparatus and Method," which described both the linear, or "picket fence," pattern and a bull's-eye shaped design .

Despite this early innovation, the practical implementation of barcodes faced initial hurdles. Early attempts, such as using ultraviolet ink, proved to be too costly and prone to fading . While IBM recognized the potential of the idea, they concluded in 1951 that the technology required to process the resulting information was not yet sufficiently advanced . The first successful commercial adoption of barcode technology occurred in the 1960s in the United States rail industry. The KarTrak system, developed by Sylvania, utilized colored reflective stripes to automatically identify railroad cars, encoding a four-digit company identifier and a six-digit car number . This demonstrates the adaptability of the core concept of automated identification through a coded system to various identification needs beyond the initial retail focus. Advancements in laser technology by Computer Identics Corporation in the late 1960s significantly improved the speed, accuracy, and reliability of barcode scanning, allowing for reading from various angles and even partially damaged labels .

The true revolution in barcode adoption came with the retail industry's embrace of the technology. In 1973, the Universal Product Code (UPC) was adopted as a standard for use in retail stores across the United States . This standardization was a pivotal moment that led to the widespread use of barcodes in retail, fundamentally changing inventory management and point-of-sale systems. The first UPC barcode scan occurred on June 26, 1974, at a Marsh supermarket in Troy, Ohio, on a pack of Wrigley's Juicy Fruit chewing gum . This event marked the beginning of the barcode era in retail. Later, to address the limitations of 1D barcodes, particularly their limited data storage capacity, two-dimensional barcodes began to emerge .

Decoding the Lines: Understanding 1D Barcodes

A 1D barcode, also known as a linear barcode, is a visual representation of data encoded in a series of parallel lines, or bars, of varying widths, separated by spaces of varying widths . These codes are designed to be read by a scanner that passes a light beam, typically a laser, horizontally across the barcode . The scanner measures the reflected light, interpreting the pattern of bars and spaces to decode the encoded data. While some 1D barcode symbologies are designed to encode only numerical data, others have the capability to represent alphanumeric characters, including letters and symbols .

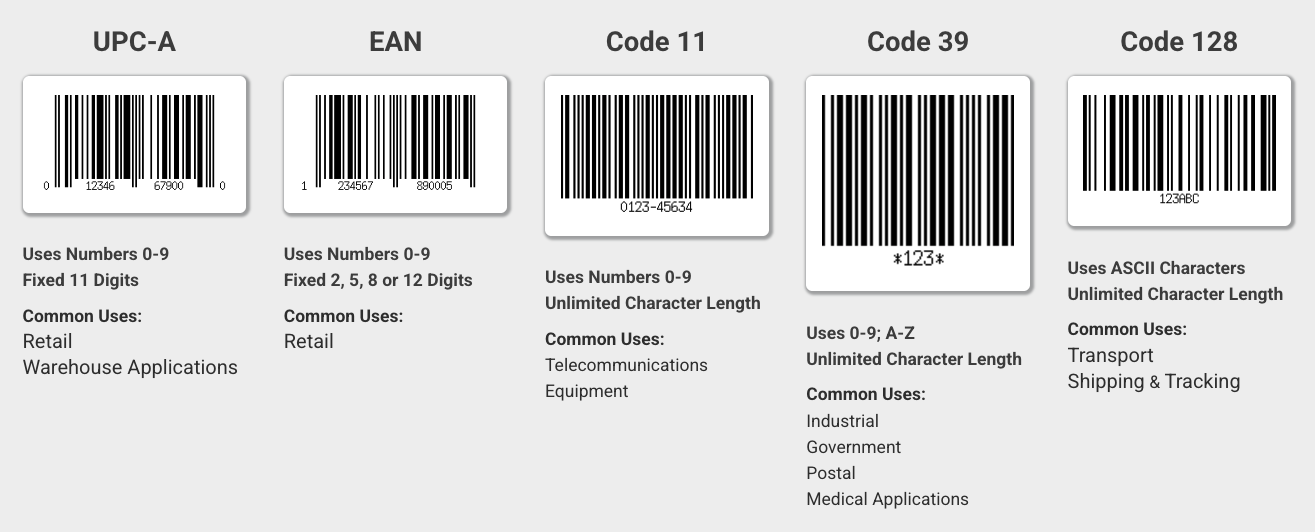

The specific way in which data is encoded in a 1D barcode is determined by the barcode symbology, which acts as the "language" of the barcode . Several different 1D barcode symbologies exist, each with its own rules and characteristics. One of the most recognizable is the UPC-A (Universal Product Code version A) . Primarily used in North America, UPC-A is the standard barcode found on most retail products at the point of sale. It consists of 12 numeric digits, which include a manufacturer identification number, a product identification number, and a check digit used for error detection . The widespread use of UPC-A in the United States and Canada underscores the regional variations in barcode usage and the importance of standardization for ensuring that products can be easily scanned and tracked across different retail systems.

The European counterpart to UPC-A is the EAN-13 (European Article Number version 13) . While originating in Europe, EAN-13 is now used globally for retail product identification. It comprises 13 numeric digits, with the first few digits indicating the country of origin or a special product category . The global recognition of EAN-13 alongside UPC-A highlights the trend towards international standards in product identification, facilitating trade and commerce across different regions.

For applications requiring the encoding of alphanumeric characters, Code 39 is a widely used 1D barcode symbology . It can encode numbers, uppercase letters, and a limited set of special symbols . Code 39 is commonly found in industrial applications, logistics, and is also used by the military under the LOGMARS (Logistics Applications of Automated Marking and Reading Symbols) standard . Its alphanumeric capability makes it suitable for tracking assets with serial numbers or batch codes, which often include both letters and numbers.

Code 128 is another popular 1D barcode symbology known for its high data density and ability to encode the full ASCII 128 character set . This includes uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, symbols, and control codes . Due to its efficiency in encoding a large amount of data in a compact form, Code 128 is widely used in shipping and logistics for identifying containers and items, in healthcare for patient identification and medication management, and in manufacturing for tracking components and finished products . It also incorporates a mandatory checksum to ensure the accuracy of the scanned data . The ability of Code 128 to encode the full ASCII character set and its high density make it well-suited for complex data encoding needs in various industries, particularly for tracking items through intricate supply chains.

Where They Shine: Common Use Cases for 1D Barcodes

1D barcodes continue to be essential tools across a wide range of industries. In retail product identification, UPC and EAN codes are fundamental for scanning items at the point of sale, which allows for quick and accurate transactions, efficient inventory management, and the tracking of sales data . For inventory management in warehouses and logistics, 1D barcodes like Interleaved 2 of 5 and Code 128 are crucial for tracking the movement and location of goods, enabling accurate updates to stock levels and streamlining the processes of sorting and picking orders . In shipping and receiving, 1D barcodes are commonly used on shipping labels to track incoming and outgoing shipments, verify the contents of packages, and ensure they reach their correct destinations . Libraries often utilize the Codabar symbology for library book tracking, allowing for efficient management of their collections and the checkout process . The healthcare industry employs 1D barcodes for various purposes, including patient identification to ensure accurate medical care, tracking medications to prevent errors, and labeling lab samples for correct processing . Finally, 1D barcodes are used for asset tracking across numerous industries to keep track of equipment, tools, and other valuable assets for inventory purposes, maintenance scheduling, and loss prevention . The wide array of applications for 1D barcodes demonstrates their enduring utility for fundamental identification and tracking needs where the volume of data to be encoded is relatively small or where the barcode serves as a key to access more extensive information stored in a database.

Beyond the Line: Understanding 2D Barcodes

2D barcodes represent a significant advancement in data encoding, storing information in a two-dimensional pattern, both horizontally and vertically . This structure allows them to hold substantially more data compared to their 1D counterparts, often encoding thousands of characters . The development of 2D barcodes was driven by the increasing need to store more information than could be accommodated by the linear structure of 1D codes. Early forms of 2D barcodes, such as Code 49 and PDF417, emerged in the late 1980s and early 1990s . However, the widespread adoption of "true" 2D, or Matrix, barcodes became more feasible with the increasing availability and affordability of camera-based scanning technology .

A pivotal moment in the history of 2D barcodes was the creation of the QR code (Quick Response code) in 1994 by Masahiro Hara at Denso Wave, a subsidiary of Toyota . Inspired by the checkerboard pattern of the game Go, Hara developed the QR code to be easily readable and capable of storing a large amount of data . Denso Wave's decision to make the specifications of the QR code public, while retaining patent rights but not exercising them, significantly contributed to its widespread adoption across various industries .

The primary advantage of 2D barcodes over 1D barcodes lies in their significantly higher data storage capacity . This allows for the encoding of much more detailed product information, including serial numbers, batch numbers, expiration dates, and even URLs linking to online resources, directly within the barcode . This reduces the need to rely on external databases for accessing comprehensive product details.

2D barcodes have found diverse applications across numerous sectors. QR codes are perhaps the most widely recognized, commonly used for linking to website URLs in marketing and advertising campaigns, providing contactless access to menus in restaurants, facilitating digital payments, and sharing contact information on business cards . Data Matrix codes are frequently employed for product tracking in manufacturing, particularly in the electronics, automotive, and aerospace industries, as well as in pharmaceuticals for serialization and traceability, and for marking small items due to their compact size . PDF417 codes are utilized in applications requiring the storage of large amounts of data, such as airline boarding passes and identification documents . In the healthcare sector, 2D barcodes are used for patient identification on wristbands, managing medication administration, and tracking medical equipment to improve patient safety and operational efficiency . The diverse applications of 2D barcodes highlight their versatility in addressing data-intensive needs across a wide spectrum of industries and consumer interactions.

Making the Choice: 1D or 2D Barcode?

Deciding whether to use a 1D or a 2D barcode depends on several key factors specific to the application. Data storage needs are paramount; if only a small amount of information, such as a product identifier, is required, a 1D barcode may be sufficient. However, for encoding more extensive data, a 2D barcode is the more appropriate choice . The available scanning technology also plays a crucial role. 1D barcodes can be read by less expensive laser scanners, while 2D barcodes necessitate the use of imagers, which are camera-based scanners, or smartphones equipped with barcode scanning applications . Adherence to industry standards and requirements is another critical consideration, as certain sectors may mandate the use of specific barcode types to ensure interoperability and compliance . Size constraints on the product or label can also influence the choice, as 2D barcodes can store more information in a smaller footprint compared to 1D barcodes . Finally, the scanning environment should be taken into account; 2D barcodes are generally more robust and can be read even if partially damaged or scanned at an angle, making them suitable for more challenging conditions .

Despite the increasing capabilities of 2D barcodes, 1D barcodes still offer certain advantages. They are generally simpler and less expensive to print and scan . The technology is well-established, with widespread support across various hardware and software systems . They can also be printed on a variety of surfaces, including corrugated cardboard for shipping purposes . Additionally, the human-readable interpretation often printed below the barcode provides a valuable backup for manual data entry in case the barcode is damaged . In some applications, 1D barcodes can offer faster scan speeds compared to 2D barcodes .

On the other hand, 2D barcodes offer significant advantages, primarily their much higher data storage capacity . They can encode a wider range of data types, including alphanumeric characters, binary data, images, and website URLs . For the same amount of data, 2D barcodes can be physically smaller . They also offer omnidirectional scanning capabilities, meaning they can be read from any angle, improving scanning efficiency . A significant advantage of 2D barcodes is their error correction features, which allow them to be read even if they are partially damaged or obscured . Furthermore, 2D barcodes can often contain all the necessary information within the code itself, enabling offline data access without requiring a connection to a database . Finally, many 2D barcode types, particularly QR codes, can be easily scanned using smartphones, expanding their potential applications for consumer engagement and information sharing.

| Feature | 1D Barcode | 2D Barcode |

|---|---|---|

| Data Storage | Limited (up to ~85 characters) | High (up to thousands of characters) |

| Data Encoding | Primarily numeric, some alphanumeric | Alphanumeric, binary, images, URLs, etc. |

| Structure | Parallel lines of varying widths and spaces | Matrix of squares, dots, hexagons, etc. |

| Scanning Direction | Horizontal (left to right) | Omnidirectional (horizontal and vertical) |

| Scanner Type | Laser scanners | Imagers (camera-based), smartphones |

| Size | Longer with more data | Compact, can store more data in a smaller area |

| Error Correction | Limited | Yes (allows reading if partially damaged) |

| Offline Data Access | Typically requires database lookup | Yes (data can be encoded directly) |

| Common Use Cases | Retail POS, inventory, shipping, libraries | QR codes, product tracking, healthcare, ID docs |

| Cost (Printing) | Lower | Generally slightly higher |

| Scanner Cost | Lower | Generally higher |

In summary, the fundamental distinction between 1D and 2D barcodes lies in their structure and, consequently, their data storage capacity. While 1D barcodes encode data linearly using parallel bars and spaces, 2D barcodes utilize a matrix structure to store significantly more information. Both types have their own set of advantages and remain relevant in various applications. 1D barcodes excel in simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and established infrastructure for basic product identification and tracking. Conversely, 2D barcodes offer enhanced data capacity, versatility in encoding different data types, robustness against damage, and compatibility with modern scanning technologies like smartphones, making them ideal for more complex and data-rich applications. The selection of the appropriate barcode type ultimately depends on a careful evaluation of data storage needs, scanning technology infrastructure, industry-specific requirements, space limitations, and the environmental conditions in which the barcode will be used. As technology continues to evolve, both 1D and 2D barcodes will undoubtedly remain crucial tools for efficient data capture and identification across a multitude of industries.